Author: Tyler Durden

Source

Authored by Ven Ram, Bloomberg cross-asset strategist,

Interest-rate traders reckon that the Federal Reserve won’t have to raise rates again in this cycle. They may be wrong.

Here are some reasons why.

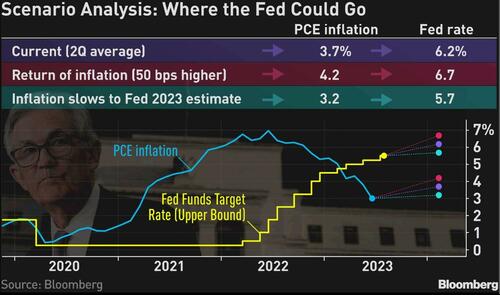

The short-term real neutral rate that underpins the US economy will reach 2.5% by the end of this year, according to researchers at the New York Fed. Given that average PCE inflation hit 3.7% in the second quarter, the Fed may be forced to tighten its policy benchmark to at least 6%.

The findings also suggest that the Fed will find it hard to cut interest rates as the market widely expects should the neutral rate remain sticky.

In that case, higher for longer may indeed turn out to be the Fed’s mantra.

The Taylor Rule rate, which is premised on a stable neutral rate, was already pointing to a higher funds rate.

The restrictive rate for the US economy is 6.55%, assuming a real neutral rate of just +50 basis points.

Neutral rate, popularly known as r*, is the rate which is consistent with an economy that is at full employment together with steady inflation.

In a recent blog post, researchers at the New York Fed led by Katie Baker contended that in the short-run r* “has increased notably over the past year, to some extent outpacing” the aggressive tightening done by the Fed in its current policy cycle.

That implies that “the drag on the economy from recent monetary policy tightening may have been limited, rationalizing why economic conditions have remained relatively buoyant so far despite the elevated level of interest rates”.

The higher neutral rate posited by the researchers is in sharp contrast to the Fed’s own assumptions as laid out in its June summary of economic projections. The central bank had assumed a real longer-run inflation forecast of 2% and a policy rate of 2.5%, consistent with a real neutral rate of 50 basis points.

There are plenty of reasons why the neutral rate may be rising. Baby boomers already in retirement and spending their nest eggs, governments running larger and larger deficits, investment in green technology and trade fragmentation may all help to tip the balance between the demand for borrowing and supply of savings.

The recent surge in real rates resonates with the findings of the New York Fed. The yield on dollar-denominated debt for 10 years reached 1.90% on Tuesday, the highest level since 2009. Nominal yields have risen in consequence, with the 10-year yield fast approaching its cyclical peak of 4.34% set in October last year.

Those are ominous signs that the real neutral rate, already running at elevated levels, may continue to rise in the coming months.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 08/22/2023 – 07:20