Author: Tyler Durden

Source

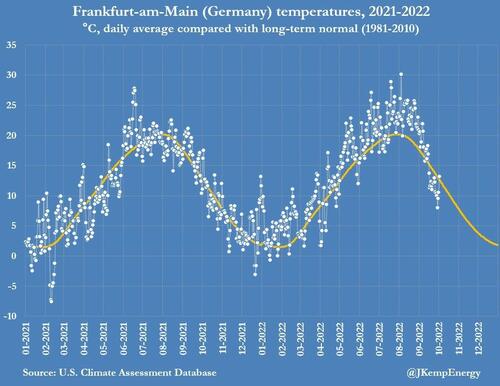

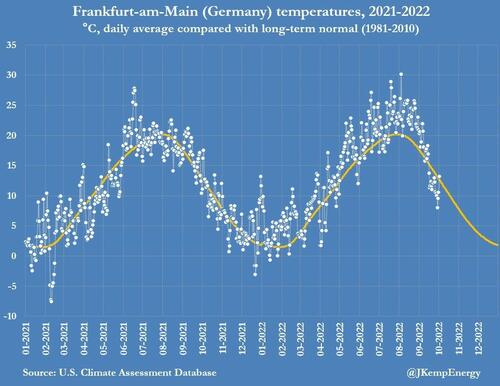

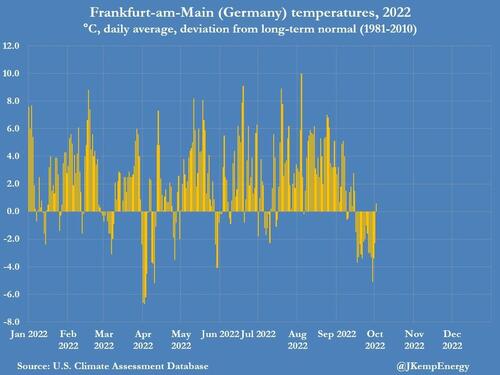

Just days after we learned that Europe’s cell phone tower energy reserves will last 30 minutes during the upcoming mass blackouts, putting the entire European cellular system in jeopardy, the continent which will soon replace Russia with the US as its vassal master and energy sponsor, got even more bad news: according to Florence Rabier, director-general of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), i.e., the European weather forecasting agency, early indications for November and December were for a period of high pressure over western Europe, which was likely to bring with it colder spells and less wind and rainfall, reducing the generation of renewable power.

This, as the FT translates, means that Europe could suffer a colder winter with less wind and rain than usual, adding to the challenges for governments trying to solve the continent’s energy crisis.

Needless to say, the forecast – which is based on data from the ECMWF and several other weather prediction systems including those in the UK, US, France and Japan – is a major problem for European politicians as they try to contain soaring energy costs for businesses and households owing to huge cuts in gas imports from Russia, and to moderate public anger and outrage at the coming freezing winter where Europe has somehow promised to cut demand by as much as 20% (nobody knows just how it will do that).

Adding insult to injury, however, is that Europe’s fascination with renewable energy will once again be a huge disappointment: “If we have this pattern then for the energy it is quite demanding because not only is it a bit colder but also you have less wind for wind power and less precipitation for hydro power,” Florence Rabier told the Financial Times.

Rabier said recent hurricanes across the Atlantic could cause milder, wetter and windier weather in the short term. But cooler weather later in the year would be consistent with the atmospheric conditions known as La Niña, a weather pattern derived from the cooling of the Pacific Ocean’s surface, which drives changes in wind and rainfall patterns in different regions.

Of course, this could prove to be just another example of Europe being woefully wrong at forecasting, well, anything (just note the ECB’s track record). Weather in Europe is difficult to predict as the conditions are dictated by several remote factors including winds in the tropical stratosphere and surface pressure across the Atlantic.

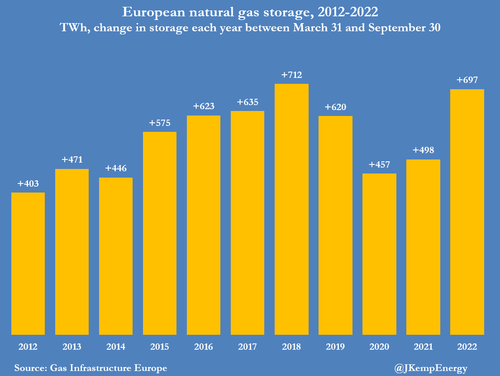

In any case, there is a faint silver lining to Europe’s coming deep freeze: as Reuters’ reporter John Kemp reports, Europe is entering winter with a near-record volume of gas in storage after buying large volumes at almost any price over the summer to prepare for an interruption of supplies from Russia.

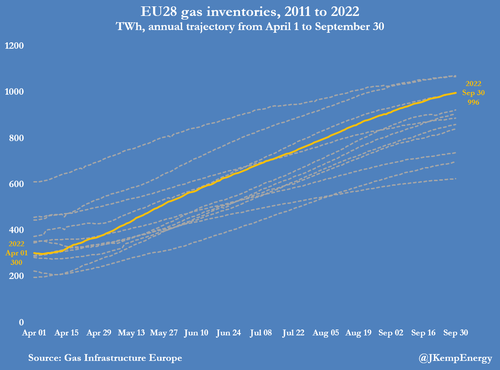

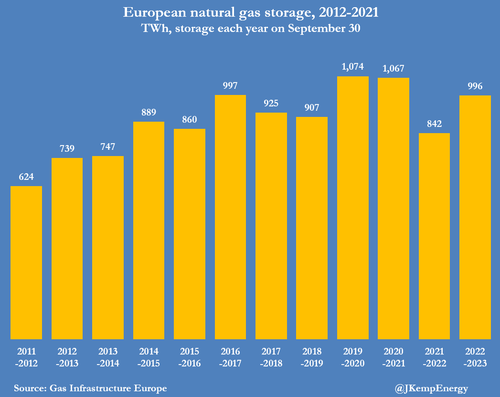

Gas inventories in the European Union and the United Kingdom (EU28) had climbed to 996 terawatt-hours (TWh) by Sept. 30, according to data from Gas Infrastructure Europe (GIE). For the time of year, inventories were at the third highest on record, with higher volumes only in 2020 (1,074 TWh) and 2021 (1,067 TWh).

Storage had risen by around 700 TWh from its post-winter low, the second-fastest increase on record, as suppliers purchased as much gas as possible despite exceptionally high prices. As a result, stocks ended the summer refill season +98 TWh (+11% or +0.83 standard deviations) above the prior ten-year average.

This is a huge turnaround from the end of January, when they were -134 TWh (-23% or -1.34 standard deviations) below.

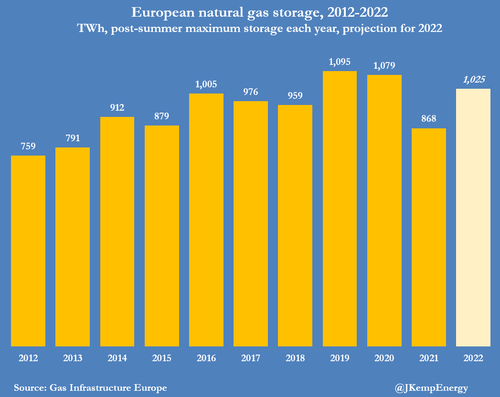

As Kemp forecasts, Inventories are likely to continue increasing for at least another three weeks until late October, but the build could persist into early November, depending on temperatures and how far high prices restrain consumption. Since 2011, the median date on which storage peaked was Oct. 26, but in two cases inventories continued rising into the first half of November.

Based on previous seasonal movements, storage is expected to peak around 1,025 TWh, with a likely range from 1,009 TWh to 1,053 TWh.

But the volume of gas in store is still increasing at an average rate of more than 2.3 TWh per day, implying it is likely to climb towards the top of the range.

Is it enough?

EU storage is more than 89% full and UK storage is more than 94% full, with extra stocks likely to be added over the next 3-6 weeks. Storage is well ahead of the formal target of 80% this year (preferably 85%) by Nov. 1 agreed by the EU in June (“Council adopts regulation on gas storage”, European Council, June 27).

According to Kemp, European governments have fulfilled their stated objective of maximizing the volume of gas in storage ahead of winter 2022/23 to reduce the impact of a disruption of pipeline supplies from Russia. But storage is intended to deal with seasonal variations in consumption, not provide a strategic reserve in case of an embargo or blockade.

Maximizing the volume of stored gas will alleviate the impact of any supply disruptions but it is not enough to guarantee supply security. In the event of a complete cessation of imports from Russia, a colder than normal winter such as the one forecast, or both, gas would become scarce before the end of March 2023.

Even if Europe scrapes through this winter, inventories are likely to end at very low levels, requiring another, perhaps even bigger, restocking next year ahead of winter 2023/24.

Bottom line: inventory accumulation has put Europe in a stronger position than at this time last year but regional supplies are still at risk which will require further action from the market and policymakers. Supply security depends critically on the ability to reduce consumption well below prior year levels – irrespective of temperatures and the level of heating demand. And if Europe has a truly cold winter, then all bets are off…

Tyler Durden

Wed, 10/05/2022 – 05:45