Author: Barry Ritholtz

Go to Source

My colleague Michael Batnick wrote a great post yesterday discussing how bear markets typically wipe out years’ worth of gains. (Before anyone leaps to an unfounded conclusion, the title of this post refers to the 2000-02 crash, and not the current weakness). Given the rough start to the new year of trading, it might be worthwhile to delve deeper into various crash scenarios for those of you who have not lived through the unwind of a bubble.

Understanding that intellectually is easy, but truly grokking the forces at work on people’s psyches during a crash is not. It is similar to warfare: perhaps you can imagine what it’s like, but only those who have lived through it truly understand the intensity and magnitude of the experience.

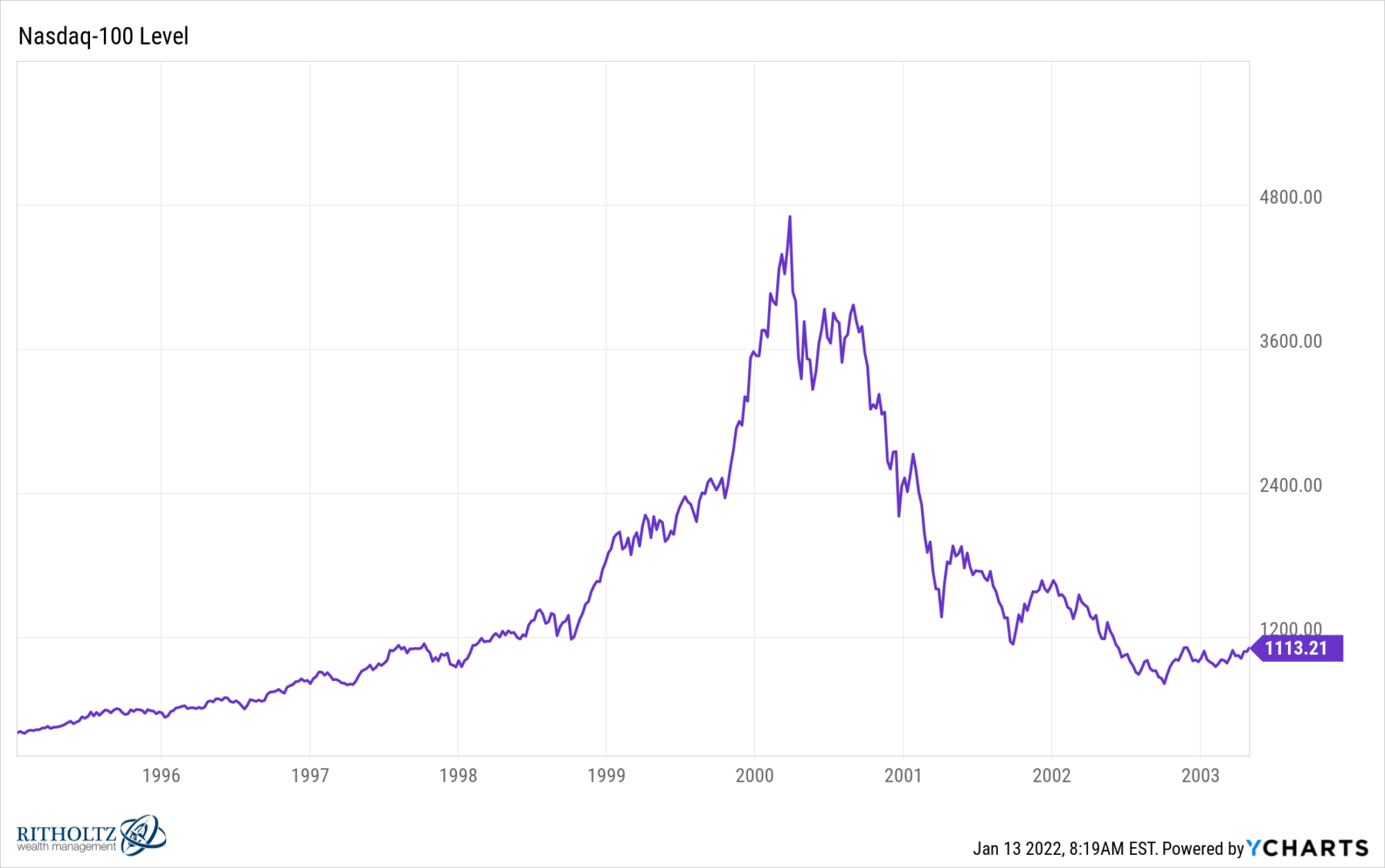

Batnick used the Dow as his example due to its long history. My frame of reference is the Nasdaq-100, traded as the QQQs. Nasdaq was where all the action was in the 1990s. I won’t bore you with war stories from trading that era; But being a trader or a strategist or a portfolio manager through the boom & crash was a once-in-a-lifetime experience; you could not help but learn about psychology, risk management, human behavior, and more (so long as you were not hiding under your desk).

We have since been through two other 30%+ crashes since the dotcom implosion: The GFC in 2008-09, and the Covid 2020 crash. But neither of those examples were truly stock market bubbles like the 1990s experience was. Here is what really stood out to me from those years:

–Skill and Experience: Good traders use many strategies to their advantage: They could pyramid, e.g., add to successful positions as they rose in price. Some averaged down (not a great strategy) but even that could work. Strategies that paid off handsomely when they were used in a 5X run over four years were less successful over the ensuing decade.

–Capital is crucial: Successful, experienced traders were rewarded with more capital and greater risk tolerances by their firms and clients. They could hold positions longer (enormously beneficial in a bull). In the days before full computerization, they could exceed their capital limits intraday. Those who were “proven moneymakers” got more ammunition to trade with, and much longer leashes.

This worked wonderfully during the 1990s phase but led to mixed results once the peak was behind us. Managing these kinds of risks is what sets apart the trading best shops (Citadel, Renaissance, GS) from everyone else that had trading disasters befall them.

–Leverage can be deadly: Some folks try to make up for a lack of capital by using leverage or options to magnify the results of their trading. That merely creates an enhanched two-sided bet — more upside, more downside. It is a risk that I suspect newbie traders on RobinHood and Reddit might not fully iunderstand yet, but (eventually) will figure out, sometimes painfully.

–Muscle Memory Persists: Investors conditioned to buy the dip take a long time to unlearn what has worked for a decade prior. The 1997 Asian financial crisis and the Long Term Capital Management collapse in 1998 each led to robust recoveries and further gains. Thosde experiences make it very difficult to break that habit.

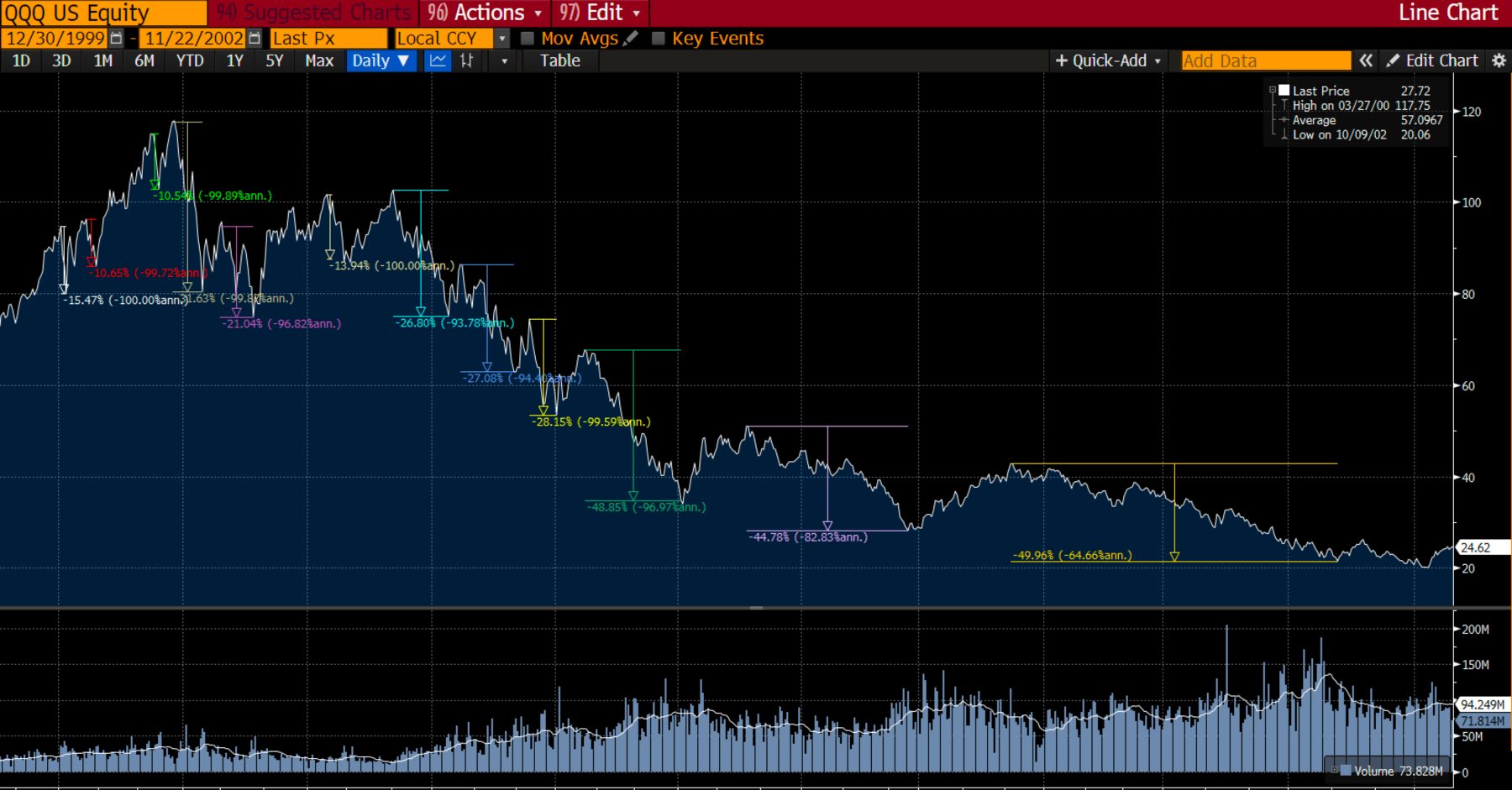

One of the things that made the March 2000-October 2002 period so pernicious was that the recoveries that followed every single drop subsequently failed. Starting in December 1999, there were drops of 15.5%, 10.7%, 31.6%, 21%, 13.9%, 26.8%, 27.1%, 28.2%, 48.9%, 44.8%, and 50%. Each one of these moves lower led to buyers jumping in to take advantage of discounts, only to see the a subsequent rally that failed. New lower lows occurred, with fewer dip buyers each time. This is how we eventually work our way towards what technicains call a sellers’ exhaustion.

–Volatility is a 2-Way Street. Risk and Reward are two sides of the same coin. Very often some of the biggest gainers with the most recent buyers give back more than average. In the 1990s, the Nasdaq outperformed the S&P500 which regularly beat the Dow Industrials. The crash saw the NDX 100 fall 82.9% (see chart at top), the S&P was almost cut in half down 49%, while the DJIA fell “only” 38%. This cycle, that has been the rotation into and out of the Work from Home stocks. As my friend J.C. likes to say, “The bigger the top, the harder the drop.”

–Regret Minimization: I have told this story before, but when you are sitting on immense gains, especially in your employer’s stock or your own start-up, taking something off of the table can be a smart move. You still have lots more stock, so if the market continues to rally you to participate but if it doesn’t you have something to show for it.

–Other asset classes lessen the pain: The popular mid to late 1990s trade was to sell some stock to buy real estate: I vividly recall clients rolling out of some equity to buy vacation properties, bigger homes, better commutes, or nicer neighborhoods. Some rationalized the swap as stocks continued to rise as a fair exchange, but they were delighted after the crash. Not everyone was so lucky.

Some last observations: I am not suggesting the current weakness is the beginning of a crash; the economy is too strong, rates are still too low, and profits remain strong. My best guess is this is likely markets digesting the gains of 2021, and adjusting to the idea of 3 or 4 rate hikes from the Fed.

Bull markets have a tendency to run much further and longer than even the most optimistic investors expect. It would not surprise me if we were still in the 5th or 6th inning of a secular bull market that continues for years…

Source:

Bear Markets Suck

Michael Batnick

Irrelevant Investor, January 13, 2022

https://bit.ly/3I65YZL

Previously:

End of the Secular Bull? Not So Fast (April 3, 2020)

Corrections & Declines (April 17, 2019)

Stealth Correction? Its Bullish, Says Batnick (October 10, 2018)

Redefining Bull and Bear Markets (August 14, 2017)

The post Living Through a Crash appeared first on The Big Picture.